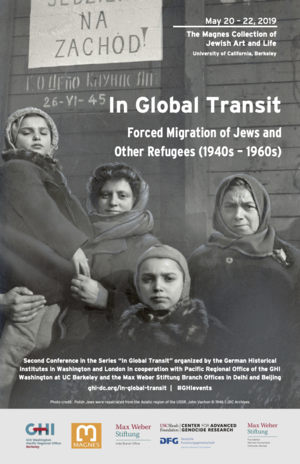

In Global Transit: Forced Migration of Jews and other Refugees (1940s-1960s)

May 20, 2019 - May 22, 2019

Conference at GHI West and The MAGNES Collection of Jewish Art and Life at the University of California, Berkeley | Conveners: Wolf Gruner (USC Shoah Foundation Center for Advanced Genocide Research, Los Angeles), Simone Lässig (German Historical Institute Washington/GHI West, UC Berkeley), Francesco Spagnolo (The Magnes, UC Berkeley), Swen Steinberg (University of Dresden)

During her welcome address, Simone Lässig raised the question of whether the Jewish experience of migration is paradigmatic. She argued that for many European refugees the search for a safe haven continued into the 1950s and that vast numbers of non-Jews in Europe were also forced to flee their homeland for a variety of reasons.

Participants of the conference were welcomed to view the new exhibit at the Magnes Collection of Jewish Art and Life, “Memory Objects.” Curators Francesco Spagnolo and Shir Gal Kochavi gave an overview of the exhibit to provide some context and introduce the objects on display. The exhibit is inspired by Warsan Shire’s poem, “Home,” and highlights the objects that migrants take with them as they are on the move. Taking both a historical and contemporary approach to migration, the exhibit reminds visitors that, since the First World War, one in seven humans are forced to be in transit. One of its highlights is a video that features contemporary migrants showing and discussing the items they brought with them as they left their homes in Syria and other places.

The first panel of the conference, titled “Borders and Boundaries,” was chaired by Anna-Carolin Augustin and devoted to the topic of Jewish refugees in Mexico and Argentina. In her contribution “Citizenship Denied: Jewish Refugees in Mexico in a Legal Limbo,” Daniela Gleizer described the “legal limbo” in which the refugees who managed to enter Mexico often remained since they faced great problems when trying to be naturalized there. Unlike Mexico, which welcomed only a small number of Jewish refugees, Argentina admitted the highest number of Jewish refugees in Latin America and regularized the status of illegal immigrants as early as 1948, as Emmanuel Kahan pointed out in his paper “Transit, Borders and Integration: Holocaust Survivors’ Travel to and Arrival in Argentina.” In contrast to the Jewish refugees in Mexico who mostly successfully participated in the Mexican economic miracle of the following years, however, Jewish refugees in Argentina were confronted with a military dictatorship. Both panelists examined the narratives of Jewish refugees in their new home countries through oral history interviews.

Overcoming several obstacles, many Jewish refugees in Mexico shared success stories after the war, which Tobias Brinkmann called an “immigration paradigm.” After discussing this and other approaches to explain Jewish migration in his keynote “Wandering Jews or Jewish Migrations? How Jewish Scholars Conceptualized Migration,” Brinkmann focused on two different migration concepts by Jewish scholars Mark Wischnitzer (1882-1955) and Eugen Kulischer (1881-1956). Both authors shared a similar origin (Russia) and migration trajectory (Berlin — Paris — New York), but came to completely different conclusions in their publications on migration. While Wischnitzer highlighted Jewish migration in his work, Kulischer, whose study Europe on the Move was to become a standard work, completely ignored the Jewish experience. Brinkmann argues that these different interpretations were closely related to their career trajectories: In contrast to Kulischer, Wischnitzer was part of a network of Jewish scholars from Eastern Europe in Berlin and well connected in the world of Jewish aid organizations. This raised the key question about the agency of Jews as migrants, which came up repeatedly during the conference.

The question of agency was addressed again in Eliyana Adler’s paper “’Send me letters and I will send you packages’: Polish Jewish Refugees around the Globe Share Knowledge and Resources” during the second panel on “Translating and Producing Knowledge,” chaired by Sören Urbansky. Adler presented case studies on Polish Jewish refugees, who shared knowledge through letters in global networks. According to Adler, these letters were an integral part of the Holocaust experience of Polish Jews across their diaspora and might be termed social capital. Razak Khan’s presentation “The Politics of Refugee Internment and Knowledge Production in Colonial India” dealt with the question of global migrant histories and in-transit archives on the basis of a case study on Leopold Weiss alias Muhammad Asad, a German-speaking Jewish intellectual in Colonial India who converted to Islam. Khan focused on individual migrant actors and the personal role they played in exile. Among other things, this panel raised the question how emotions drive knowledge production.

The third panel, chaired by Indra Sengupta and titled “Conflicting and Converging Identities: Emotions in Transit,” put Björn Siegel’s paper “We were refugees and carried a special burden”: German Jewish Emigre?s and the Emotional Struggle of Finding a New Home in Sa?o Paulo,” in conversation with Sarah R. Valente’s paper titled “Post-World War II Brazil: A New Homeland for Jews and Nazis?” about refugees in Brazil to highlight a reoccurring theme of this conference: the search for home. Whereas Siegel emphasized the emotional aspect related to exploring new national and communal identities in new spaces, Valente’s focus was spatial. In her presentation, she looked at the co-existence of Jewish survivors and escaped Nazis as they lived in the same geographical spaces in Brazil.

South America was also the focus of the fourth panel, titled “Production and Use of Networks in Transit” and chaired by Claudia Roesch. Sandra Gruner-Domic and Nancy Nicholls Lopeandia delivered talks about Bolivia and Guatemala and Chile respectively. In her paper, “World Sojourners: Jewish Migration to Bolivia and Guatemala,” Gruner-Domic utilized archival sources and oral histories of Jewish Holocaust survivors in Bolivia and Guatemala to undertake a more focused study on what it means to be “in transit.” Her work highlights how global networks enabled the passage of some Jews from Europe through Bolivia and Guatemala as they searched for a safe final destination. Lopeandia’s focus on Chile under Pinochet in her paper “‘We are not going to wait until 1939 … this is 1933’: The Role of Popular Unity Government and Pinochet’s Dictatorship in the Holocaust Survovors’ Decision to Emigrate to Chile” shows how survivors’ experiences during the Holocaust influenced their decision-making during the upheavals brought about by a rising socialist regime, a coup d’état, and finally a dictatorship. She concluded that in several cases memory of the Holocaust affected how individuals and families navigated their life in Chile during these moments.

During the fifth panel, on “Refugees in Processes of Decolonization, State Building, and State Crisis,” chaired by Isabel Richter, Pallavi Chakravarty presented her paper “Notun Yehudi (the New Jews): A Study of the Refugees from East Pakistan in Post-Partition India.” Chakravarty focused on the similarities they drew to the experiences of Jewish refugees from Europe, such as the adaption of the metaphor of the Jew-in-Exile and their desire to return home. Margit Franz devoted her contribution “’Shifting Figures in a Shifting Landscape’: Holocaust Refugees in Young Independent India” to a small group of Jewish refugees from Europe who had fled to India, where they became ambassadors for internationalism in the arts and a cosmopolitan culture and participated in India’s nation-building efforts through art.

The sixth panel, on “Power Structures and Shifting Settings: Class, Race, and Gender,” chaired by Andrea Sinn, opened with Atina Grossmann’s paper “Trauma, Privilege, and Adventure: Jewish Refugees in Iran.” Based on the micro-history of her parents, Jewish refugees who had fled from Berlin to Iran, Grossmann emphasized Teheran’s special historical significance as a place for Jewish refugees in global transit and the associated history of empire and anti-colonial struggles. The intersection of Jewish exile with colonial history also played a key role in Natalie Eppelsheimer’s paper “Haven in British East Africa: German and Austrian Jewish Refugees in Colonial Kenya.” Taking African history into account, Eppelsheimer pleaded for a critical engagement with the colonial setting and a discussion of the fact that the grounds on which the Jewish refugees had settled in British East Africa were highly contested.

The papers discussed during the seventh panel, “Departing as Child — Arriving as Adult: Age and Generation,” which was chaired by Sheer Ganor, centered on bringing various narratives of migration together, including flight, remigration and integration. Anna Cichopek-Gajraj’s “‘Living Across Border’: Agency and Displacement of Polish Jewish and Ethnic Polish Migrants after the War (1945–1960)” sought to go beyond the standard narrative of DP camps and seemingly fluid migration to the U.S. Her focus was on the journeys themselves, or the “transit,” but with the caveat that migrants did not necessarily perceive themselves as being in transit or “in-between” places. Transit, she remarked, as did others in the conference, is a notion that develops for people in hindsight. Andrea Orzoff’s paper, “Musical Migration: Ruth Scho?nthal from Mexico City to New York,” highlighted the story of musician Ruth Scho?nthal to illustrate the impact that Central European cultural émigrés had on the Latin American musical world. She also demonstrated how music could be the foundation for one’s identity beyond the notion of belonging imposed upon migrants by the nation-state model.

How to find or determine one’s “home” was the question connecting the two papers in the eighth panel, titled “Neighborhoods between Belonging and Alienness” and chaired by Nick Underwood. In her paper “American Dreams: Jewish Refugees and Chinese Locals in Post-World War II Shanghai,” Kimberly Cheng took a novel approach to the history of Jews in Shanghai. By placing their experiences within the Chinese context, Cheng showed how, while in Shanghai, Jewish migrants began to develop an American national identity, which they embraced in order to contextualize and unpack the fomenting Chinese resentment towards Jewish refugees. Yael Siman’s presentation “Home and In Transit Location for Holocaust Survivors in Mexico” focused on Holocaust survivors’ immigration to Mexico, highlighting complex networks and the difficult journeys that many made to get there. Utilizing oral histories from the USC Shoah Foundation Visual History Archive — as many of the contributions on Latin America at the conference did — she painted a vivid picture of how these Jewish migrants reacted to their new home in Mexico.

The ninth panel, “Narrating Transit and Forced Migration,” chaired by Andrea Westermann, also centered on Latin America. In her paper, “From Auschwitz to Bogota?: When Genocide and Political Violence Converge,” Lorena A?vila Jaimes revealed the experiences survivors had in Colombia, which included having to face war and political conflict in two very different geographical and cultural contexts. By focusing on neighboring Bolivia, Helga Schreckenberger in her paper, “Bolivia as Transitory Refuge: Memoirs of Jewish Refugees,” explored why refugees were unable to establish a more permanent home for themselves there. She noted that many refugees in Bolivia found it hard to give up their adherence to a definitively German cultural space, which made their adoption of and integration into Bolivian culture that much more difficult.

In the concluding discussion, Wolf Gruner presented a summary of the main issues and questions raised during the conference. In particular, he broadened the various dimensions and different approaches of global transit that had been discussed in the individual panels. Terms and concepts were discussed afterwards, for example, similarities and differences to other terms like migration or global displacement. It was clearly expressed that the individual refugee experience and narratives must always be taken into account in the terminology as well. It was also stated that the history of knowledge is clearly linked to the history of migration and transit and can provide useful concepts. Multilingualism and imagined journeys are two further closely related issues that should be considered in connection with the history of global transit.

This was the second conference in a series dedicated to migration history. The next conferences will probably focus on forced migrations more broadly so that researchers can begin to develop studies that highlight coping strategies and think about forced migration as a form of knowledge production. Specifically, the conferences will seek to determine, among other things, what knowledge is needed to maneuver bureaucracy and consider objects as part of a history of forced migration.

Anna-Carolin Augustin (GHI Washington) and Nick Underwood (GHI Washington)

Call for Papers

This conference is the second in a conference series devoted to people “In Global Transit.” The first conference, which took place in Kolkata in 2017 focused on Jewish and political refugees from Nazi-controlled Europe who fled, at least initially, to European colonies or countries of the global South.

“In Global Transit: Forced Migration of Jews and other Refugees (1940s-1960s)” will build on the 2017 conference, taking a broader perspective and expanding the geographic and analytical focus. It will examine the experience of Jewish refugees who found haven — but not new homes — in Asia, Africa, and Latin America. For most of these individuals, the end of the war did not mean an end to life in transit. To the contrary: after a period of temporary settlement, they found themselves not only once again on the move, but also in a new, more ambiguous situation. On the one hand, growing awareness of the Nazis’ attempt to wipe out European Jewry called attention to the plight of the Jewish refugees. But, on the other, they were just one among many groups in search of permanent homes as the large-scale expulsion of ethnic, religious, and/or national groups became a global phenomenon. The ever-more frequent waves of involuntary migration, in turn, provided the impetus for the development of an international refugee policy — a process in which onetime refugees from Nazi-controlled Europe played a notable part.

The conference “In Global Transit: Forced Migration of Jews and other Refugees (1940s-1960s)” aims to illuminate the particularities of (usually) involuntary Jewish migration from and between countries of the global South that have received little scholarly attention thus far. We seek, moreover, to use the experience of Jewish refugees as an analytical prism to consider the phenomenon of forced migration more generally. Jews were part of European and worldwide flows of migrants of unprecedented scale and diversity. Among those migrants were individuals, such as the Nazis and Nazi collaborators who fled to South America, North Africa, and the Middle East, whose experiences hardly fit narratives of victimhood. Most societies at the time were not prepared to deal with mass movements of refugees caught “in transit,” and, needed new knowledge and legal instruments in order to respond. That new knowledge was produced not least of all by Jewish legal experts and social scientists who drew on their own experience of life in transit.

The conference will look beyond established turning-points and consider long-term refugee movements between socially and culturally disparate countries and regions. Jewish refugees from Nazi-controlled Europe will be taken as a paradigmatic group to explore basic questions about the transit experience, for example, the question of the relationship between knowledge and modes of dealing with contingency and uncertainty. An important related issue is the tension between the simple desire to survive and the challenge of planning for a life in a new, unfamiliar setting. We are particularly interested in the encounters between Jewish refugees and members of other groups they encountered while in transit countries, such as other refugees, colonial subjects, and religious or ethnic minorities subject to discrimination.

We are particularly interested in the following topics and areas of inquiry:

- Coping strategies that refugees developed during various phases of transit and in shifting settings to deal with transience, uncertainty, and unpredictability: What role did circumstances such as residence in a refugee camp, opportunities for employment, and dependence on material assistance play in the development of coping strategies? What types of knowledge were needed or deemed necessary to manage uncertainty? Which practices and which networks evolved from them? Who were the actors in the exchange of knowledge and who targeted sharing of knowledge for coping? How important were categories such as generation, age, gender, origin, social status, and family? How far do concepts such as adaptation and identity offer insight into the “transit mindset”?

- Power structures that affect trans-migrants locally and on larger, national, regional and global levels: What was the relationship between officials and refugees, between bureaucratic practices and the experience of forced migration? How did different state and non-state actors like aid organizations, resettlement agencies, employment bureaus, and even Jewish communities etc. react and get involved with regard to migrants with different ethnic, religious, professional or class background? What role in particular did local Jewish communities and the local representatives of international aid organizations play as disseminators of knowledge or as producers of knowledge?

- Knowledge production in the course of and as a product of generally involuntary global transit: How did the experience of life in transit influence the development of new concepts such as statelessness and human rights or anti-colonialism and development policy? How did that experience shape perceptions and interpretations of anti-Semitism and racism? The Americas are as pertinent as other regions of the world in addressing these questions.

- Material dimensions of flight and transit: How did the importance of material possessions change from one phase of transit to the next? What were forced migrants allowed to take with them? How did that vary over time and place? How did possessions shape the route of migration or affect the duration of the period of transit? What roles did specific objects play? What value do surviving objects possess as historical sources? We are also interested in the economic importance of possessions and topics such as the sale of possessions to escape harm. Which actors were involved in the transfer of property as refugees were in transit? Who profited from such transfers?

- Visual and artistic representations of flight and transit: What images and portrayals of life in transit did those involved produce? Which forms of representation were developed in the situation of transit? How do the diverse literary treatments of the refugee transit experience relate to scholarly analyses of that experience? What aesthetic continuities and/or discontinuities are evident in the work of refugee artists?

If you are interested in discussing these or related questions, please send a brief CV and a proposal of no more than 300 words by August 1, 2018, to Heike Friedman (friedman@ghi-dc.org). Lump sum travel grants will be provided to successful applicants.